Twenty years since my heart transplant in March 1990

Edward (second from right) celebrating the wedding of his eldest daughter Annabelle. From left: Emma (born two years after his heart transplant), Annabelle’s husband Nick, Annabelle, Sue (his wife), Edward, Eliza (his middle daughter).

These following words are from an article Edward wrote in 2010. An updated version can be read by downloading a recent article shared in Issue 101 of the Circulator.

CLICK HERE to download Edward's updated story

In sharing my own personal reflections I hope that my thoughts can be of support to others. People awaiting a heart or lung transplant look death in the face. It is a humbling experience. In the face of death I am sure that everyone contemplates the meaning of life. For me it was a time when I reflected on my life.

Now when I read stories written by heart/lung transplant recipients, it is clear to me that these stories come from real people who have looked beyond their troubles even when the going seemed impossible. They have made the best of their situation climbing back up and starting life again.

In Melbourne all transplant patients receive the strongest support and encouragement from the Alfred Hospital. I notice that in addition to always acknowledging the hospital transplant recipients give unstinting praise to the organ donors and loved ones who have given them support during their ordeal. I am inspired and amazed at the capacity of people to fight and survive and I am sure this determination plays a key role in recovery.

Both my parents lived into old age. I am now in my seventies, the second youngest of six children all of whom still live productive lives. My eldest sister is well over eighty and enjoys good health. Until the age of fifty-three I had not had a day's sickness in my life and I was dumbfounded when I was told that I had cardiomyopathy.

The cardiologist who diagnosed my illness, the late Dr. William Heath, was a family friend. Both his parents had died when he was a teenager. He brought up his younger siblings in the country and after qualifying as a doctor he ultimately reached the top of his profession. He left a lasting impression on me during my illness by emphasising that with courage and determination adversities which look insurmountable can be overcome.

When I had been feeling unwell and first visited Dr Heath, I was running an engineering company which operated in Australia, New Zealand and South East Asia. I had founded and built up this business over thirty years. I mention this because receiving the news that I was unwell, not only came as a shock but as a huge challenge to deal with this business which I had established.

At the time I had four children, the youngest only one. I believe that it is those who love us, who go through the greatest trauma in all this. In my case, my wife never showed her distress but always continued the daily routine as if life was normal. She did so many things for me to occupy those long drawn-out anxious days of waiting. In due course I was accepted on to the waiting list for a heart transplant.

For a period of about nine months I was largely confined to my bed. Anyone awaiting a transplant will find this a debilitating time. I developed shingles. To this day I still have chest pain resulting from that virus. There were times when without the incredible support given to me by my wife and by Dr Heath, who called on me almost daily, I would have found it difficult to pull through.

He had many stories to tell which brightened my day and when I now look back I remember those stories and realise how very small things that we do in support of others in their time of need, can make a great difference.

Listening to the radio one day while lying in bed I heard of a Scottish immigrant who had started a factory in Altona making haggis. I had never tasted a haggis and my wife telephoned the owner. She explained my condition asking at the same time if she could drive me out and see the factory. The owner gave me a wonderful tour of all stages of manufacture and then presented me with a haggis free of charge for my dinner.

Waiting for my transplant I had mixed emotions. On the one hand I was desperately waiting for the telephone to ring knowing full well that time was running out; on the other, every time it did ring I was too timid to answer it in case it was the real call from the Alfred. It was only on my third call and visit to the Alfred that the operation took place.

The first two occasions were unpleasant experiences when it didn't turn out to be my chance. On the third occasion it was late in the afternoon that the hospital telephoned. All that day I had been looking forward to a special dinner being prepared by my wife and of course I was told that I could not have any food as I was required in the hospital in a couple of hours time.

At the Alfred I had been fully prepared for the operation when the anaesthetist said to me that I could be in for a wait. He asked me to relax and to take my mind off the impending operation tell him about something which I had been doing recently. Of course there wasn't much to say but I did notice that he spoke with a Scottish accent and so I decided to tell him about my visit to the haggis factory. Some days after my operation, my wife showed me the Herald-Sun which had published my haggis story given to the newspaper by my anaesthetist.

A family friend of Greek nationality, familiar with the hospital system in Greece where patients supply their own food, had prepared meals for my stay at the Alfred. The food was left in the staff-room refrigerator with my name on each dish, a meal of grilled whiting, another of duckling, rare beef, chicken, together with a variety of all different deserts and cheeses.

I was told by the nurses that my food had filled their refrigerator. I was very limited in what I could eat and I was teased by the nurses. They would come into my room each day and tell me how much they were enjoying each dish and especially the deserts and cheeses.

It was my first stay in a hospital and I must say the early hours of the morning were a hard time for me as a trolley would pass my bed at about four o'clock. I was sure that on the trolley was the body of a person who had died during the night, being then taken out draped in a sheet. I tried to use the trolley with the body as an excuse to get out of the hospital but I was told that the trolley only contained dirty linen from the night shift. I was anxious to get out of the hospital in time for my daughter's third birthday but it was quite a battle with Dr Esmore.

Finally he allowed me to go and I did make my daughter's third birthday party. The wonderful but cautious Dr Esmore, who we all hold in the highest regard, achieved a world record with me - I was up and out of the hospital in ten days able to resume normal life.

My youngest daughter who is now sixteen was born five years after my transplant. The Transplant Clinic gave my wife and me a warm welcome on my visit to the Alfred after the birth. Post transplant I have enjoyed an active and wonderful life with my wife and children.

To people awaiting transplant who might read my story, remember that the greater the challenge you overcome in your life, the greater your reward. Stay strong and focus on your future beyond transplant surgery.

Twenty years on, when I take my medication, I remember the generosity of my donor family and think of those living through the same trauma that I experienced not so long ago.

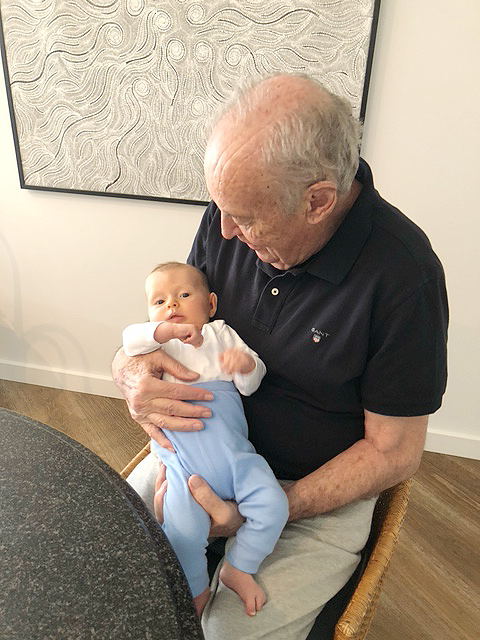

My wife Sue, mother of our three girls, holding Oliver, our first grandchild. Sue has been my greatest companion and supporter through the transplant journey, especially the last few years which have been very challenging with my neuropathy.